Written by Gavin Fraser, Senior Blue Ocean Expert

Since I conducted my classmates beating drums, triangles and clappers at the age of 6, it has been my dream to one day conduct and make the best recording ever made of some of the greatest music ever written, Mozart’s last two symphonies, numbers 40 and 41.

But dreams don’t suddenly become real. Along the way for me, this meant gaining a Bachelor of Musicology through part-time study and many years later attending conducting lessons and masterclasses.

I finally felt prepared, but the challenges to create my dream recordings were enormous: How could I be certain that “the best recording ever” as I perceived it would resonate with buyers and users and create a leap in value for them? How would I find high quality musicians and persuade them to break with centuries of convention and create the sound I was looking for? How would I record and mix the music in an unprecedented way so as to create a leap in the clarity and definition of the sound of an orchestra? And would the cost be prohibitive and how could I cover it?

Without being steeped in blue ocean thinking for the last 27 years this dream would have remained just that. Blue ocean thinking provided the focus and guide to make important choices and refine what were initially only unclear instincts on my part, as well as the confidence to undertake this journey and turn the dream into reality.

Exploring Noncustomers

The blue ocean process starts with exploring noncustomers of a target industry. Exploring their pain points will reveal the assumptions and boundaries that limit the appeal and size of the industry and open up opportunities to create leap in value for buyers. This is where I started.

I was surprised to find that, of regular listeners of classical orchestral music, dissatisfied users – what we call Tier-1 noncustomers, dominated hard-core fans by about 10 to 1. A common issue for them is that many of the recordings which have received high praise and awards in the past were recorded 50 years ago or more. Recording and mixing technology have advanced by leaps since those times making older recordings sound rather “muddy” and “undefined” however nuanced the musical phrasing is or how ‘right’ the tempo feels. Tier-1 noncustomers also complained about the almost complete loss of some instruments and the dominance of others in the recordings. They further complained about the lack of excitement in the breadth of sound: older recordings meant for vinyl had a limited sound range.

And to my surprise again, those who refused to listen to classical orchestral music (Tier 2 noncustomers) or those who were never considered as potential customers of classical music recordings (Tier 3 noncustomers) actually listened to and enjoyed a lot of relatively complex orchestral music in the soundtrack music to video games and films they loved. Some raved about attending symphony concerts focused specifically on the music from their favorite video games whilst giant screens project images from these same games.

The fabulous inside of the jewel case created by the graphic artist in Egypt showing Mozart looking across at his wife, Constanza, his English friend Nancy Storace and King George III of England. Mozart is poised in mid-air, seeking to fulfil his dreams by getting to England. Sadly, for all of us, he died before this was possible.

Reconstructing Market Boundaries

Juxtaposing noncustomer insights with the six paths frameworks of blue ocean strategy allowed me to create the best recording ever through reconstructing across conventional boundaries.

Orchestral gaming music and film tracks, for example, offered a depth of bass sound and sparkle and ‘presence’ at the top end not often heard in classical music which sounded “boxy” by comparison for non-fans of classical music. Video game and film music also offered clearer definition between different parts, better music and sound effects and the feeling of being in a large open space when listening. By contrast, classical recordings sounded distinctly “mono”. By combining the best of what these alternative industries offered and introducing more clarity and a wider dynamic range and sound depth into my Mozart recordings, I would create a leap in value for all listeners.

Searchability is another major issue for classical orchestral music recordings. Whereas popular music can be found by the artist or band name and album name, classical music albums have many more potential searchable items such as the composer, conductor, orchestra, particular work, movement and featured soloist, but these may or may not yield a result at all. Sometimes multiple works are put together to fill a vinyl or CD; conductors may even cut out repeated sections of the music to offer additional works, further compounding the search issues since there are multiple works on a single album. By reconstructing across different strategic groups of the musical recording industry, I would offer the complete version of each Symphony online separately, in addition to a physical CD or online version of both Symphonies together. This would make my recordings searchable as well as include all the music Mozart wanted us to hear.

Furthermore, by looking across complementary product and service offerings, I came to the idea of including the background information about how and under what personal circumstances Mozart composed these two symphonies in the digibooklet through iTunes or on Facebook or a website. This would help listeners build a more profound connection to the music. Besides, with this approach, there would be no need to translate the information into multiple languages for international listeners, since the top search engines offer translation to a multitude of languages at the touch of a button.

The emotional-functional orientation was also one path I looked across. In Mozart’s time, when a section of music was repeated, there was a simple way of indicating this in the score using a symbol like a colon without having to write it all out again. However, did the composer intend the music to be played exactly the same way each time? Apparently not –that would be boring and void of nuance and subtlety. Yet, many recordings do just that, which is a rather functional approach to the music. I decided that not only would I produce a recording with all the music the composer intended to, but also create a different sound for every repeated section of music to better express the intent of the music at that point. This would involve bringing out more a particular instrument or internal melodic line or making subtle changes to rhythmic emphasis during a repeated section.

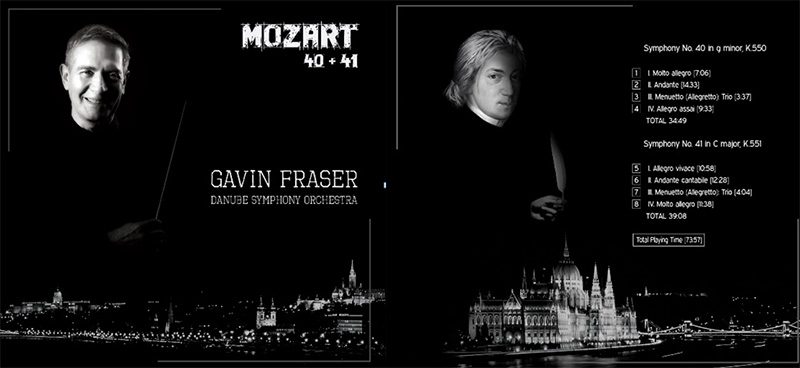

The outside cover of the CD version of the two symphonies together.

A Dream Come True at Low Cost

Now I had a clear idea of what a best recording ever would be like, the next question was how I could realize this dream with a viable business model. My objective was to achieve breakthrough value at low cost.

The recording supply chain had to be low cost. I initially considered hiring an existing orchestra from Eastern Europe. But that meant the additional costs of resident conductors and management. I started with freelance musicians instead who tend to know one another as they meet to perform in ‘pop-up’ orchestras. I searched for a “kingpin” – someone who knew many talented musicians. I found one and then I had musicians! I felt massively privileged to be able to access all this talent for my project at fairly modest rates.

The next question was, how was I going to get the musicians to play each note exactly as I wanted them to without spending hours of time rehearsing (often with one group of players whilst the rest of the orchestra would be somewhat bored)? First I wrote in their musical scores (parts) the micro details of exactly how I wanted them to play each note using a combination of accepted music symbols and Italian words of expression. Then I organized a session with the leaders of each section – my orchestral “kingpins” in blue ocean terminology – and rehearsed the music. I then paid them and the rest of their sections to rehearse at their own convenience at any time and place that suited them. This approach saved an enormous amount of time and money while making the musicians more comfortable and productive.

Then came the challenge of how to record classical orchestras in high quality at low cost. The industry ‘standard’ way of configuring microphones – the so-called ‘Decca tree’, used just a few microphones to create an acceptable stereo ‘sound stage’. This approach was economical but had the risk of creating another ‘muddy’ recording. I decided to combine the accepted industry standard use of the Decca tree with the use of multiple additional closer microphones, and then isolate the instruments as much as possible to achieve the higher definition and control that is the hallmark of popular music and film sound tracks. To avoid the prohibitive cost of doing this, I resorted to my kingpin, who introduced a recording engineer – one of the best in Europe – with access to one of the best studios in the world and the means to obtain all the microphones needed at no extra cost.

Once the recording was done, I needed to find the right mixing engineer. I looked for sound engineers with film industry experience rather than strictly orchestral music mixing experience. I found half a dozen and sent them part of the recording of one movement and paid an incredibly modest sum for just 50 seconds of their response to the kind of sound I wanted. After hearing the works of sound engineers in the USA, UK, South Africa, Germany, Hungary and France, I decided on a mixing engineer in southern France.

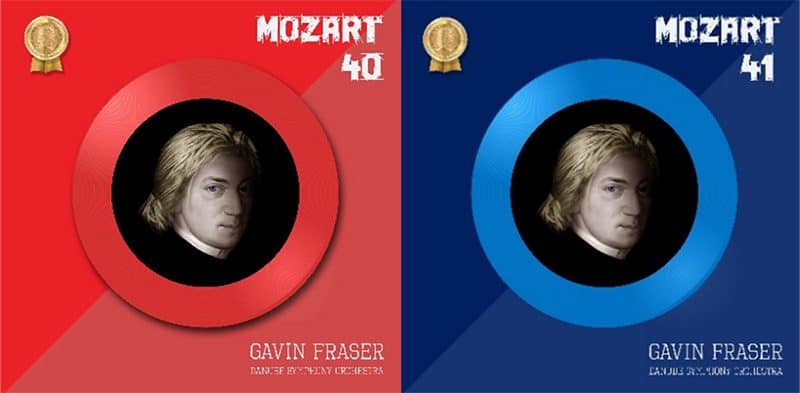

Similarly, I reached out to potentially thousands of talented graphic artists through an Internet site. Overnight I received dozens of replies to my rather vague proposal, and within days I had found two highly talented artists – a lady in Egypt who would create the surreal inside of the CD case and a gentleman in the UK who would create the artwork for the outside of the ‘jewel case’ for the physical CD. He would also use part of this artwork to create the all-important single symphony versions which would feature on streaming sites.

The final step was manufacturing the CDs and also accessing an ‘aggregator’ to interface with iTunes, Amazon, Google and Spotify. Once again, after an Internet search, I found a charming boutique firm in Scotland who provided a one-stop service to do both for me, hassle-free.

The symphonies were launched in late July 2018.

Initial Response

The initial response has been fantastic. Since their launch, the CDs are regularly in top position on streaming sites such as Spotify and Googleplay, and moving up the ranks of sites where you have to pay to download. No marketing investment has yet been made. The differences in these recordings are quite apparent to people and I am amazed at the thousands who have listened to them in just a few weeks on many different platforms.

As a ‘cherry on the top’ one famous conductor with his own orchestra kindly wrote to me when he heard Symphony 41, “I thought there were only three living conductors who knew how to conduct Mozart properly, and now I know there is a fourth. I listened to your remarkable achievement eventually in tears”.

Final Thoughts

We all have dreams. Often the way to make them real is unclear, or we believe we lack the necessary resources. Blue ocean principles provide the guidance and roadmap for achieving our dreams and help us break the trade-off between value and cost.

The recordings are available in the double symphony version (mostly for physical CD sale through Amazon) as well as the single symphony versions on Spotify, iTunes, Apple Music, Amazon Music and Google Play. Search ‘Gavin Fraser Mozart Symphony 40’ or ‘Gavin Fraser Mozart Symphony 41’.

For an illustration of the sound that I have tried to achieve, try the first minute of Symphony 41and listen out for the oboe at 31 seconds in: the sound may remind you of ‘Gabriel’s Oboe’ in Ennio Morricone’s fantastic score for the film ‘The Mission’. Click here and select the second track down called ‘Andante Cantabile’.

Also try the last track, called ‘Molto Allegro’ for the same Symphony for the first 1 minute 30 seconds to hear the clarity of sound, particularly from 1 minute 5 seconds onwards. Finally, listen right at the end from 10 minutes 35 seconds until the end to hear those drums!

The covers for the online single symphony versions.

By Gavin Fraser

About the author

Gavin Fraser is a senior expert on Blue Ocean Shift | Strategy | Leadership, and senior faculty of the Blue Ocean Global Network