The legal industry is highly competitive, but finding new customers doesn’t have to be a cutthroat business. Otabek Suleimanov, a partner at Central Asian law firm, Centil, explains why the firm set out to make a blue ocean shift, the pain points it uncovered for clients, and the results it’s already starting to see. The firm shows how to shift from the cutthroat competition in the legal industry.

What is the current state of the legal industry in Central Asia?

Central Asia’s legal market has been developing for the past 15 years. Prior to this, national law firms were usually involved with local clientele, while international law firms serviced foreign clients who were investing or trading in Central Asian countries (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan).

The situation began to change in the mid-2000s when national law firms started acquiring a bigger share in the international clientele market. Also, a rise in business activity and investment in the region have boosted the development of national firms.

In particular, many large international law firms have entered Kazakhstan, which is the region’s biggest economy – its GDP is five times bigger than the combined GDP of all the other Central Asian countries. The size of the entire Central Asian legal market is currently about USD 50 million.

Why are Central Asian law firms in a red ocean of cutthroat competition?

The entire legal market in Central Asia is a red ocean of cutthroat competition with all firms pursuing one primary objective: to increase their market share. Firms tend to follow the same pattern: stick with existing clients, pitch for more projects, provide better prices, hire better lawyers, and so on.

Our market analysis indicates that market share is more or less evenly distributed among local and international law firms, and the entire ‘competition’ takes place within these market boundaries. Pricing is the major competitive instrument. Law firms usually implement a policy of predatory pricing to win the pitch rather than offer anything beyond conventional products and specializations.

All firms continue to repeat the mantra of ‘quality’, which is an unmeasurable and ephemeral concept that adds no value as a proposition since it is assumed that all firms are offering high-quality products and services.

Certain assumptions that define the industry include hiring ‘star’ lawyers, specializing in as many areas of law as possible, working with hourly rates and fee caps, having cluttered websites with lots of unnecessary information, and drafting all documents manually.

Where did you see pain points for clients?

Centil works in emerging markets. When international clients and investors attempt to research the jurisdictions within the region, they often fall short. There is a lack of well-written English-language information to help them navigate the legal, environmental and legislative frameworks in the region.

A major pain point for foreign investors and financial institutions operating within Central Asia is the lack of reliable analytical data that would help them to make better decisions. Our competitors, i.e., other Central Asian law firms, generally offer just legal services without giving clients a broader picture of the investment environment as they prepare to do business in the region.

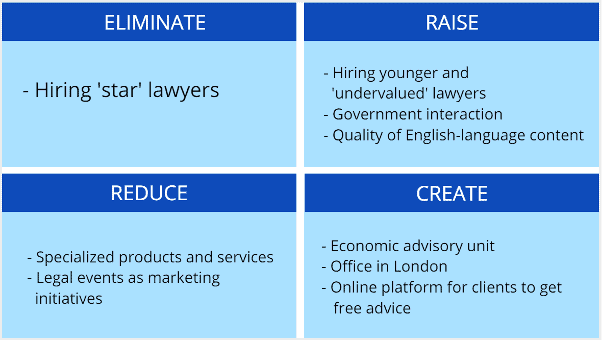

What factors did you eliminate and reduce in your offering?

We stopped hiring ‘star’ lawyers, as they often bring more hype than actual value. Instead, we hired more young and undervalued lawyers. This is important because, to build a business that is not just profitable in the short term, but sustainable in the long term, you need to nurture and develop home-grown partners who share the firm’s principal values and fit well with the internal corporate culture. This is much easier to achieve when someone’s early career is supported and developed within the firm, rather than outside of it.

We also reduced the number of specializations we offered. Corporate law firms tend to advertise dozens of specializations (for example, tax law, insurance law, construction, contracts, etc.). However, we reduced these down to two major products: corporate and finance. We selected these core offerings as they match the needs of our existing customers and, more importantly, our noncustomers who invest primarily in our region, trade with companies located in our region or finance big regional infrastructure projects via loans. Rather than offering a broader spectrum of legal services, we saw an opportunity to add value to the major core legal products on which we had focused for the past decade.

We also reduced our spending on things that other firms often invest in, such as hiring as many specialists as possible or frequently attending legal events as a marketing initiative. Instead, we spend our money on raising the value of our offer.

The eliminate-reduce-raise-create (ERRC) grid © Chan Kim & Renee Mauborgne.

What factors did you raise and create in your offering?

Instead of expanding into other legal specializations, we invited a group of economists and analysts to join the team. We currently have 12 experts who make up the firm’s economic and business advisory unit. By establishing this unit, we can bridge the knowledge gap that is a pain point for so many clients in the region. The unit offers clients market analysis, cost-benefit analysis, policy impact assessment and strategic planning.

We also increased our interaction with governments, starting with the Uzbek government. Traditionally, law firms have distanced themselves from the government, never seeing it as a profitable client. However, the arrival of a new and more liberal president in Uzbekistan is changing things, with the government now willing to reach out to consulting firms to get help in attaining its objectives.

We increased our presence in London, which is a major marketplace for our typical customers and noncustomers. Other things we raised include the creativeness, quality and quantity of our English-language content.

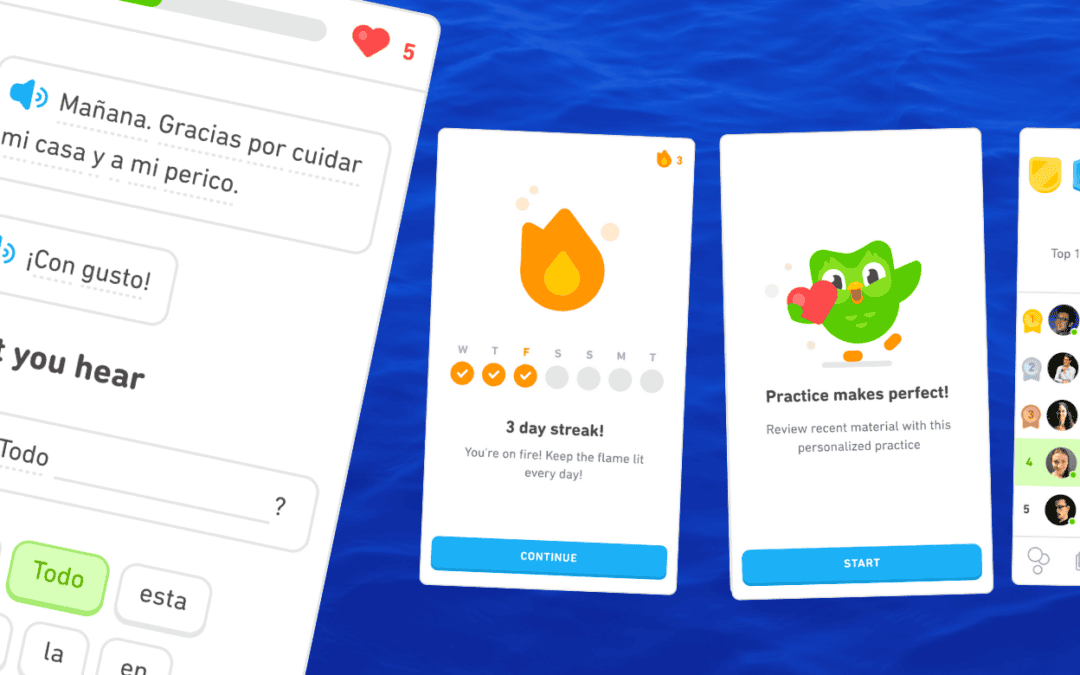

We have also created electronic platforms where clients can get free advice; software that will eventually create corporate documents, significantly reducing manual work; and more focused content, optimizing our use of resources.

What are the initial results since embarking on your blue ocean shift journey?

Since beginning our blue ocean shift, our blue ocean approach has made us unique in the region and set us apart from the rest of the market, avoiding cutthroat competition. We’ve been pulling in prestigious noncustomers including the Uzbek government, state-owned corporations, the business departments of several of our existing clients in the petrochemical and energy sectors, as well as the analytic departments of numerous development banks. Other wins include working with major international management consulting firms, who rarely approach law firms when they conduct projects in our region. Our customer satisfaction scores are going up and sales are increasing by double digits. The number of visitors to our website has almost doubled in last 12 months, an unprecedented jump for us.

Centil was shortlisted for The Lawyer’s “Law firm of the year: Russia, Ukraine & the CIS” Award in both 2017 and 2018 (the winner of the 2018 award is due to be announced in March 2018). We were also honoured to win The Law Society’s “Award for Excellence in International Legal Services” in 2016, after being shortlisted alongside much bigger international law firms. Tellingly, The Law Society cited Centil’s “dedicated research and analysis branch” and “innovative approach to managing knowledge and disseminating business intelligence” as reasons why Centil ultimately won the prestigious international award.

Ultimately, we feel that our search for our own blue ocean has united our people and that we are on the right track. A butterfly is not merely a more sophisticated version of a caterpillar, but rather a completely new organism with its own unique qualities.