The Indian Premier League (IPL), reinvented the nation’s cricket league by transforming a long-winded ‘gentlemen’s game’ into a thrilling three-hour sports drama featuring Bollywood stars.

It created a new market space known as ‘cricketainment’ whereby cricket is played and enjoyed in a completely different way from all other cricket games. It unlocked huge demand from audiences that had previously ignored or rejected the traditional form of the game.

The Indian Premier League: a huge and immediate sporting success

The IPL league is contested by eight teams representing eight cities in India. Fans of the game get to see some of the best cricket players in the world while enjoying Bollywood music and entertainment from cheerleaders during the intermissions.

For Indians, cricket is more than a game. As the dominant sport in India, it has a massive fan base throughout the country. It is also the highest-earning national sport. It’s strong sponsorships and star players generate 60% of cricket revenues worldwide.

The inaugural season of 2008 was watched by 200 million Indians on TV and 10 million overseas viewers, overtaking the record 150 million viewers that had previously tuned into football’s English Premier League. The IPL became the world’s sixth-biggest sports league within two seasons.

What is cricket and what are the rules of the game

Similar to baseball, cricket is a bat-and-ball team sport. Each team is composed of 11 players, with teams taking turns to bat and field. The objective of the game is to score more runs than the other team, with the batsmen creating runs by striking the ball and running the length of the pitch at the center of the field. The fielding side aims to dismiss the batsman by hitting the wickets behind him or catching the ball after it has been hit, but before the ball hits the ground.

Originating in England in the 16th century, cricket is the world’s second most popular sport after football. Influenced by the British Empire, today’s major cricketing countries are members (or former members) of the Commonwealth, including Australia, India, Pakistan, and England itself.

The red ocean of Indian cricket

The Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) is the governing body that regulates all cricket matches played in India. Until 2008 the BCCI was swimming in a red ocean of competition. It had monopolistic power, operated in a lucrative industry, and was the richest sports body in India. As such, the BCCI had little incentive to change or innovate the way it operated. Many organizations in this position focus on what they are comfortable doing. Content with the status quo and well equipped to outdo the competition, they don’t see a need to innovate until it is too late.

The BCCI focused on increasing the number of cricket matches rather than creating new value for cricket fans. The league seemed set up more for the sake of the players than for spectators and failed to attract mass attention.

Not surprisingly, Indians were much more interested in the international cricket matches played by the national team than the domestic championships. On top of that, the BCCI was not run professionally and for the good of the game – revenue never trickled down to improve infrastructure or support local cricket talents. As such, there opened up a large chasm between two strategic groups: national teams and local teams.

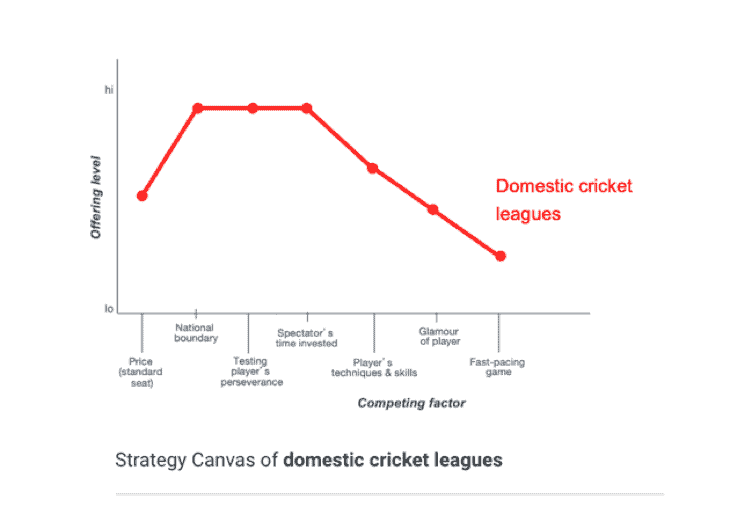

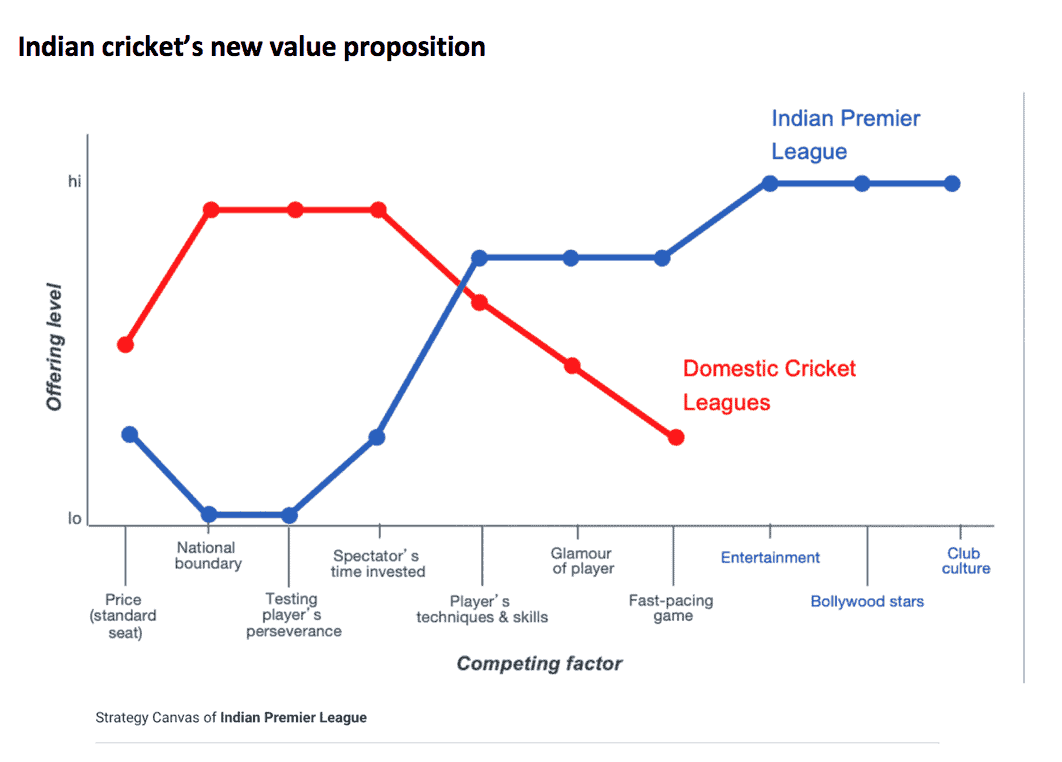

The as-is strategy canvas of the domestic cricket league

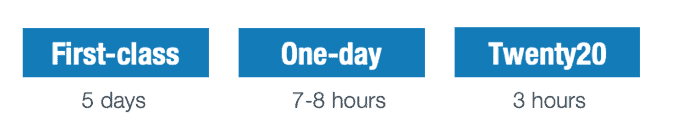

The as-is strategy canvas of the domestic cricket league helps us understand the red ocean scenario of Indian cricket. At this time, domestic cricket leagues were played in either Test (five-day) or ODI (one-day) formats among the local and regional cricket associations. Competing factors included limiting players to national boundary and calling on players and spectators to invest time and perseverance in the game (see below).

Introducing a faster-paced game – Twenty20 cricket

In England, in 2003, a new format was introduced to cricket, offering spectators a fast-paced alternative to the longer, traditional forms of the game. Twenty20 cricket is a more TV-friendly version, lasting three hours per match. As opposed to test- and one-day cricket, Twenty20 is a faster, more aggressive game. Each team is only given twenty overs (120 balls) to score runs. Initially rejected by traditional cricket fans for ruining the tradition and style of cricket, Twenty20 is now overwhelmingly popular—76% of cricket viewers prefer Twenty20 over test- and one-day cricket. It was this format of the game that the BCCI adopted for the IPL.

Creating a Blue Ocean in Cricket: The strategic logic behind the launch of the Indian Premier League

1. To unlock new demand, look into noncustomers, not customers of your industry

The BCCI fundamentally shifted the strategy of the cricket industry. It began by reorienting its strategic focus from competitors to alternatives and from customers to noncustomers of the industry.

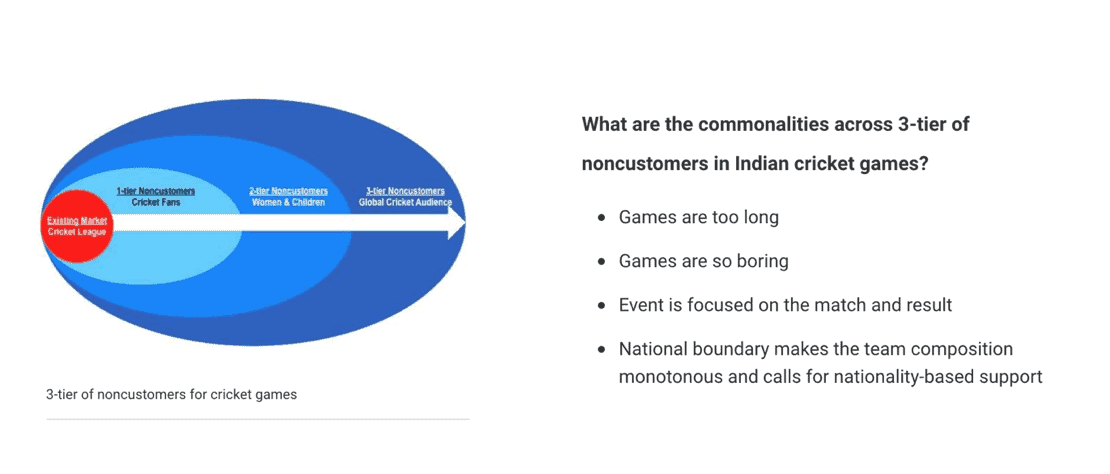

The three tiers of noncustomers framework, developed by Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, illustrates the noncustomer analysis for the cricket industry. To unlock the biggest demand, the BCCI focused on commonalities not differences among the three tiers of noncustomers.

The first tier of noncustomers is made up of general cricket fans, who support the Indian national team out of patriotism in international events. They turn into noncustomers as soon as India is knocked out of an international tournament. For instance, in the 2007 Cricket World Cup, India was defeated in the very first round. As a result, the viewership rating plummeted from an average of 7.5 to 1.6.

The second tier of noncustomers comprises people, especially women and children, who find cricket’s complicated rules and rituals difficult and the matches long and boring. These noncustomers refuse to watch a game that takes five days to crown a winner. The game itself is not fun, as it is played for the players, not for the spectators. Moreover, it is too hot to sit outside for an entire day.

The third tier of noncustomers is the global cricket audience, who only care about cricket in their own countries. For instance, Australian cricket fans are unlikely to find India’s domestic league interesting, as they are played by unknown players to a relatively low standard.

- Reconstructing market boundaries

The first principle of blue ocean strategy is to reconstruct market boundaries to break from the competition and create blue oceans. This principle addresses the search risk many companies struggle with. The challenge is to successfully identify, out of many possibilities that exist, commercially compelling blue ocean opportunities. There are six paths to remaking market boundaries, which Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne call the six path framework.

To see a detailed analysis of these paths, check out the free online interactive IPL case study which goes into blue ocean tools and frameworks in depth.

For now, let’s look at one of the paths to see how it is done.

Path1: Look across alternative industries

Path 1 challenges the fundamental assumption that underlies many organizations’ strategies, keeping them trapped in red oceans. It challenges organizations’ natural inclination to define the industry similarly and focus on being the best within it.

BCCI looked at the alternatives to cricket and what other forms of games or entertainment were popular.

Traditionally, cricket was played to test the players’ physical and mental perseverance instead of creating a dynamic and thrilling spectator sport. The IPL shifted the focus of the game to the cricket viewers and offered them what they valued the most, incorporating activities from a professional football league and the entertainment industry. In so doing, the IPL reconstructed market boundaries and created the league of cricketainment (cricket + entertainment), which is unlike anything seen before in the cricket world.

The BCCI first looked across prominent sports leagues, such as the English Premier League (EPL) of the United Kingdom and the National Football League of the United States. Many viewers from all across the world stay up late to watch the EPL. These viewers have no ties to England. The BCCI wondered why anyone from outside the UK would be so passionate about the football league and its teams, even including people who knew little about the game.

The reason was simple. EPL matches were often breathtaking and dramatic, played by the best players in the world. Stars of the game like David Beckham were as famous as Hollywood celebrities, often with a devoted following. A world-class game played by glamorous players made this domestic football league globally recognized and commercially successful.

The BCCI looked next across alternatives for Indian leisure activities, such as watching TV, going to the cinema, and dining at restaurants. Bollywood, in particular, has been an essential part of Indian life regardless of age, gender, and caste. As TV is the most accessible form of low-cost entertainment for Indian families, people of all backgrounds are pulled to the TV set to watch Bollywood dramas and shows. Bollywood entertainment contains dramatic stories, stirring emotions, and spectacular performances delivered by glamorous celebrities.

Compared to other forms of Indian entertainment, cricket was viewed as serious and impractical. Few Indian families could watch the game for six hours a day or five consecutive days (sometimes without a winner) even if they wanted to.

By looking at alternative industries, the BCCI could draw value factors to make the cricket league fun, exciting, and charming.

Indian cricket’s new value proposition

The strategy canvas of the IPL (above) depicts its distinctive value proposition to cricket viewers as compared to a one-day cricket international match, such as the Cricket World Cup. While the existing cricket leagues followed the same conventional logic as the Cricket World Cup, the value curve of the IPL diverges from that of the Cricket World Cup by focusing on the fun and thrill of the game. The IPL becomes even more compelling by offering unprecedented value, looking across alternatives like the EPL and Bollywood drama.

As a result of creating an unprecedented cricket league, the IPL reached beyond existing demand. It turned all three tiers of noncustomers into cricket lovers.

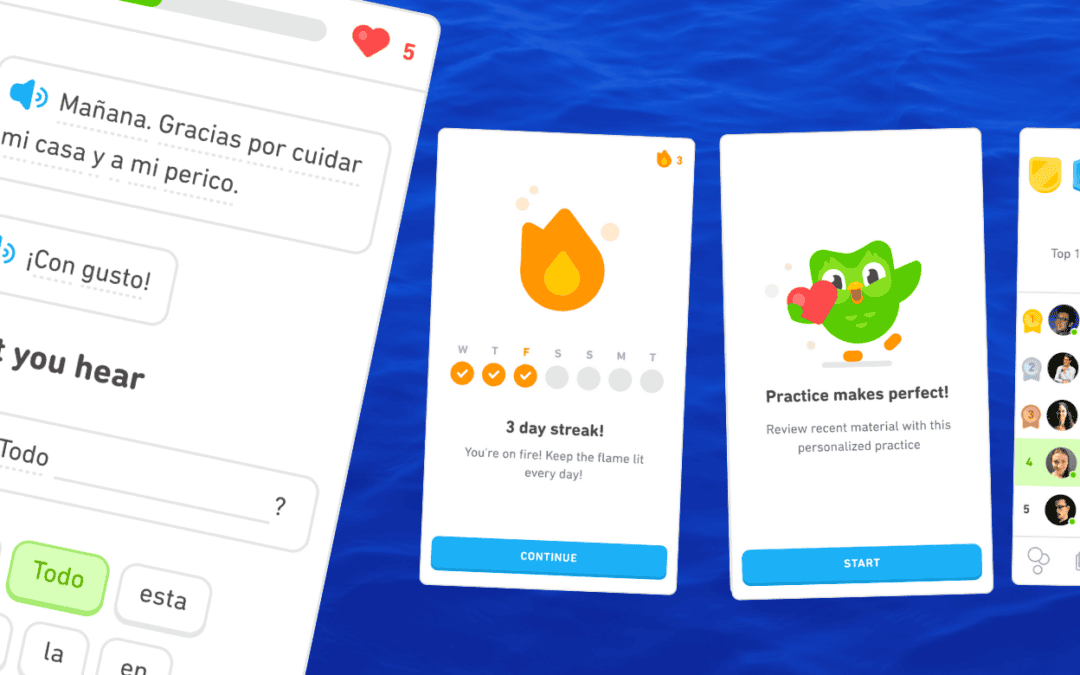

To learn how IPL achieved value innovation and created a leap in value for the people, partners and BCCI itself, go through this online interactive case study.

Today, the Indian Premier League final is like the Super Bowl

The inaugural IPL season was more than a success. Over 200 million Indians watched the debut season. During the semi-final and final matches, 50% of Indian households with cable or satellite TV watched the IPL.

Want to explore the Indian Premier League case study in more depth? Check out our interactive online case study.