Written by Michael Olenick, Institute Executive Fellow at the INSEAD Blue Ocean Strategy Institute.

Few product failures are as well-known as the Segway electric scooter the two-wheeled electric scooter that promised to revolutionize transportation. In this article, we’ll explore how the makers of the Segway might have used the buyer utility map, a key tool of blue ocean strategy, to predict and avoid product failure.

Why Segway failed – A ‘cool’ technology nobody wanted

In June 2020, the much-heralded Segway electric scooter finally met its demise with production slated to end immediately. The two-wheeled self-balancing machine is often cited as the ultimate flop.

Introduced to enormous fanfare in 2001, few people besides police in pedestrian and shopping malls found much use for the machine. They were too big for sidewalks, too slow for streets, too heavy to carry into offices, and too expensive for everybody. But at their launch, they were seen as a cool, breakthrough technology.

Segway case analysis: From Segway to e-scooter

Despite its failure, the Segway did evolve into a vehicle that delivered much of what the original offering promised: electric scooters or ‘e-scooters’ for short. E-scooters are battery-powered two-wheel scooters that whisk people around urban areas. If you’ve been to any large city or college town, you’ve seen them.

E-scooters cost 90-95% less than Segway electric scooters while offering more value. They’re small, lightweight, easy to transport in cars, and on busses and trains. They can be carried in stores and recharged at work. E-scooters offer the utility that Segways promised – being able to effortlessly zip around – but at a small fraction of the cost.

Scooters don’t self-balance like the Segway, but they’re far more useful and convenient for getting around. Arguably, the biggest drawback of e-scooters is they do not offer the exercise that walking does.

The Segway electric scooter was ‘cool’ technology nobody wanted.

Segway case study: The Segway is a prime example of technology innovation

At their introduction, the best minds in technology were awed by the self-balancing device. The Segway “will be to the car what the car was to the horse and buggy” said the inventor, Dean Kamen. Countless people believed him. Famed venture capitalist, John Doerr, predicted the Segway would be “bigger than the internet.”

Kamen was no stranger to innovation having previously released a long string of successful medical devices. The Segway itself was based on a wheelchair he designed that stood on two wheels to go up and downstairs.

Others thought that a non-polluting, electric, self-propelled device was a great idea that suffered a botched execution. “Its shape is not innovative, it’s not elegant, it doesn’t feel anthropomorphic,” said Steve Jobs.

In any event, the public didn’t see enough value in the Segway to purchase a meaningful number of the $5,000-devices.

Kamen had recognized the value the Segway was supposed to offer, especially compared to cars. “Cars are great for going long distances,” he said, “but it makes no sense at all for people in cities to use a 4,000-lb. piece of metal to haul themselves around”.

However, by loading the Segway with too much technology, he increased the price and size to the point where it didn’t make much sense to buy or use the machine.

Technology innovation vs value innovation

Technology innovation is the creation of a product or service feature that focuses on new or improved technology. Often, the technology is cited as the differentiating factor. The utility of the technology is put front and center, with an expectation that buyers will find a use for it either now or later.

The Segway electric scooter’s key attributes were that it self-balanced on two wheels and had a battery that made it capable of scootering all day without the need to recharge. In hindsight, the self-balancing was gimmicky – it looked cool but offered little real utility.

Furthermore, it was dangerous for people who could not already balance on a scooter or bicycle. The big battery was unnecessary as people tend to scoot to places where they can recharge. Few people, if any, need to zoom around on a scooter all day.

Finally, the large form factor made the Segway impossible for sidewalks or streets, too large to bring to office buildings, and an eyesore when stored at home. The price was entirely out of sync with the utility the Segway offered.

Why Segway failed? Unlike e-scooter, it didn’t offer value innovation.

E-scooters are an example of value innovation

E-scooters, in contrast, are an example of what Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne call value innovation, which is the cornerstone of blue ocean strategy.

Value innovation is the simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low cost. E-scooters are a good example of value innovation: an offering that solves real-world problems in a way that makes the competition irrelevant. Learning from the mistakes of the Segway, the makers of e-scooters took the idea of a self-powered mobility device and turned it into a successful business.

E-scooters have batteries strong enough to power journeys between a few locations, but they’re also lightweight enough to be plugged in and recharged at an office. E-scooters require users to balance on two wheels, but their low center of gravity makes balancing easy. They’re faster than walking but need virtually no physical effort.

Finally, e-scooters are small enough to be easily stored in a house or apartment, carried in the trunk of a car, or brought onto public transport.

The value proposition the Segway promised was recognized with the creation of the e-scooter.

Segways, e-scooters, and the buyer utility map

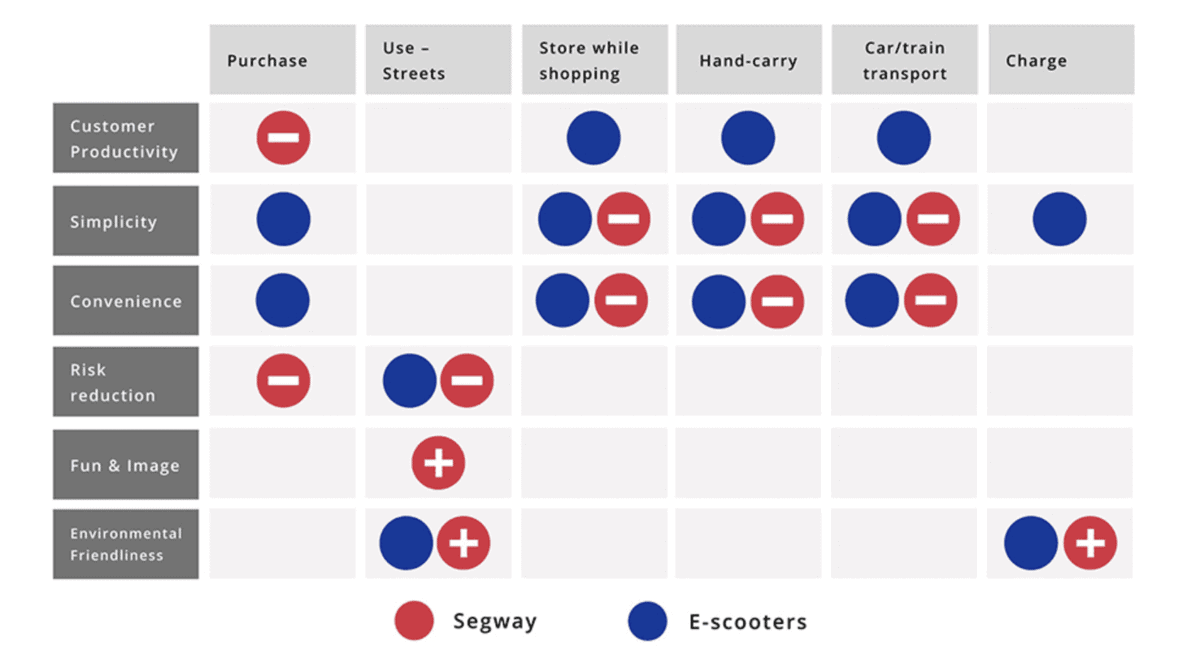

The buyer utility map is a blue ocean tool to assess whether potential buyers – customers, but more importantly, noncustomers – find adequate utility in a proposed product or service. Buyer utility maps visually show whether a product or service unlocks substantive buyer value and differentiation.

The map consists of two dimensions. Across the top is the buyer experience cycle, the steps a would-be buyer encounters through the lifecycle of a product or service.

The books Blue Ocean Strategy and Blue Ocean Shift lay out six common steps in the buyer experience cycle: purchase, delivery, use, supplements, maintenance, then disposal. These six steps can change depending upon the proposed product or service.

For personal transport devices, we’ve identified the following as our buyer experience cycle: purchase, use on streets, store while shopping, hand-carry, carry in cars or public transport, and charge.

On the vertical axis are the utility levers that never change. These are customer productivity, simplicity, convenience, risk, fun & image, and environmental friendliness.

Blue Ocean Strategy Buyer Utility Map: Segway and E-scooters

© Chan Kim & Renée Mauborgne, Blue Ocean Shift: Beyond Competing – Proven Steps to Inspire Confidence and Seize New Growth.

The red circles indicate where the industry or existing offering typically focuses. In the case of the Segway, plotted in red, we’ve marked some cells with a plus (+) sign if the attribute differentiates from the larger industry (such as the car industry) and a minus sign where there is little or no incremental value.

The blue circles show our new offering, the e-scooter, where the intersection of the experience cycle and utility lever offers breakthrough value.

As we can see below, the buyer utility map could have predicted the demise of the Segway or the success of e-scooters.

Let’s examine a few cells to see how this works.

On the left, for purchase, the Segway is marked with a red minus sign for customer productivity and risk. That’s because Segways were purchased from dealerships, like cars, that required special trips and training. Buying a Segway was a hassle.

Furthermore, at $5,000 and with its large size, buying a Segway was an expensive and risky proposition.

In contrast, buying e-scooters is simple and convenient. They can be purchased from a myriad of sources, online and in stores. Online channels have countless product reviews and comparisons and stores have in-person help. After purchase, the e-scooter can be easily carried home by hand or in the trunk of a car and used with no training.

We’ve repeated the exercise for each column and row. There are some cells where Segways and e-scooters both offer positive utility that cars do not, marked by a plus (+) sign for the Segway and a blue dot for the e-scooter. Specifically, they’re both more environmentally friendly than cars.

Summary

As the exercise and the map illustrate, the demise of the Segway and success of the e-scooter were predictable. None of the plot points are counterintuitive nor especially difficult to predict. Even before its release, several news articles discussed the blocks to utility apparent in the Segway.

However, the company – and their investors – were apparently fascinated by the admittedly fun technology and chose not to listen. That’s too bad because they might have unlocked utility for the world, and a large business for themselves, earlier and at a far lower cost than the Segway cost to develop.

About the author

Micheal Olenick is an Institute Executive Fellow at INSEAD Blue Ocean Strategy Institute.