“Every company wants one, yet only a few companies have one: a compelling strategy,” write Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne in their classic Blue Ocean Strategy. Don’t despair if you don’t know how to create a strategy that stands out in a sea of me-too competitors. In this blog, we’ll introduce you to one of the blue ocean strategy tools, the Strategy Canvas, that will help you stand out from the crowd and create a blue ocean of new market space. To understand the power of the strategy canvas, we’ll look at five powerful examples from a range of industries.

About the strategy canvas

The Strategy Canvas is a central diagnostic tool developed by Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, world-renowned professors of strategy and bestselling authors of Blue Ocean Strategy and Blue Ocean Shift.

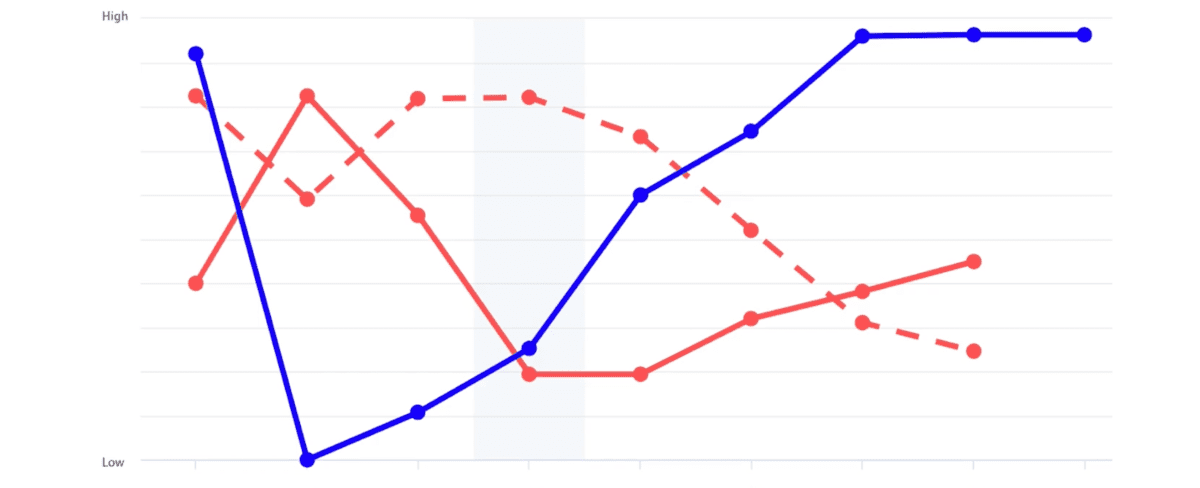

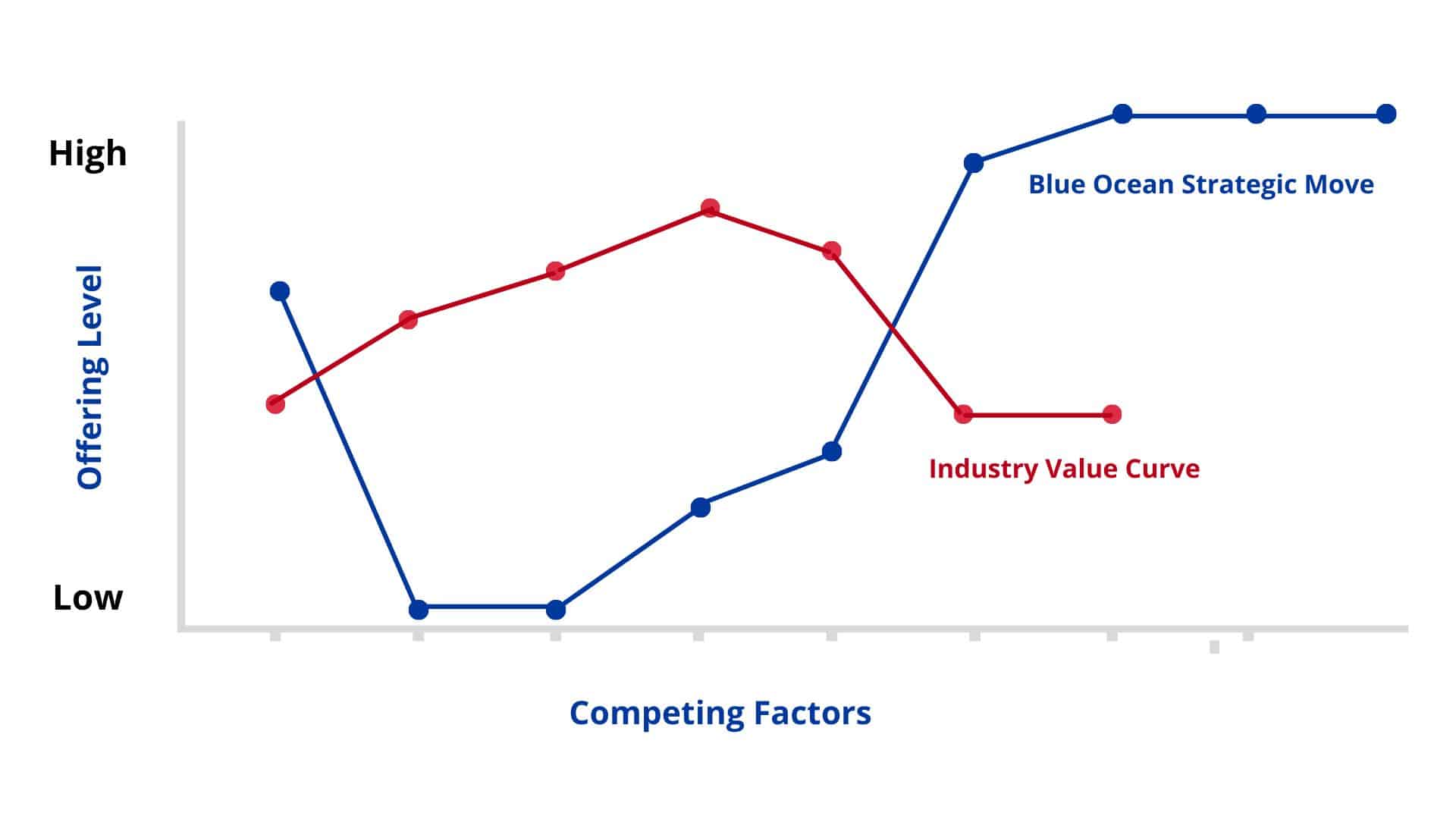

The strategy canvas captures the current state of play in the known market space, which allows users to clearly see the factors that an industry competes on and invests in, what buyers receive, and what the strategic profiles of the major players are.

It exposes just how similar the players’ strategies look to buyers and reveals how they drive the industry toward the red ocean.

A value curve, or strategic profile, is the graphic depiction of a company’s relative performance across the factors of competition in its industry. It shows how your company’s strategy fares against the competition.

Strategy Canvas

The strategy canvas is one of the key analytical tools and frameworks of blue ocean strategy. (c) Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne. All rights reserved.

3 Characteristics of an Effective Blue Ocean Strategy

When expressed through a value curve, an effective blue ocean strategy has three complementary qualities: focus, divergence, and a compelling tagline.

1. Focus

– a clearly defined strategic profile or value curve helps companies avoid trying to be everything to all consumers

2. Divergence

– breaking away from the industry’s standard value curve to stand apart from the competition

3. Compelling tagline

– delivering a clear, truthful message that accurately reflects your strategic profile is a good way to test for a truly effective strategy

Learn more about the three characteristics of a good strategy in our strategy vs tactics blog.

Now let’s look at some compelling examples of strategy canvases to clearly see how these organizations exemplified an effective blue ocean strategy.

5 Strategy Canvas Examples to Inspire Your Quest for the Blue Ocean

Apple’s iPhone

A powerful strategy canvas example in the mobile phone industry

Perhaps more than any other company, Apple captures what it means to have a blue ocean perspective. Its ‘think different’ approach led the company to make a series of blue ocean strategic moves that reconstructed whole industries and changed the world.

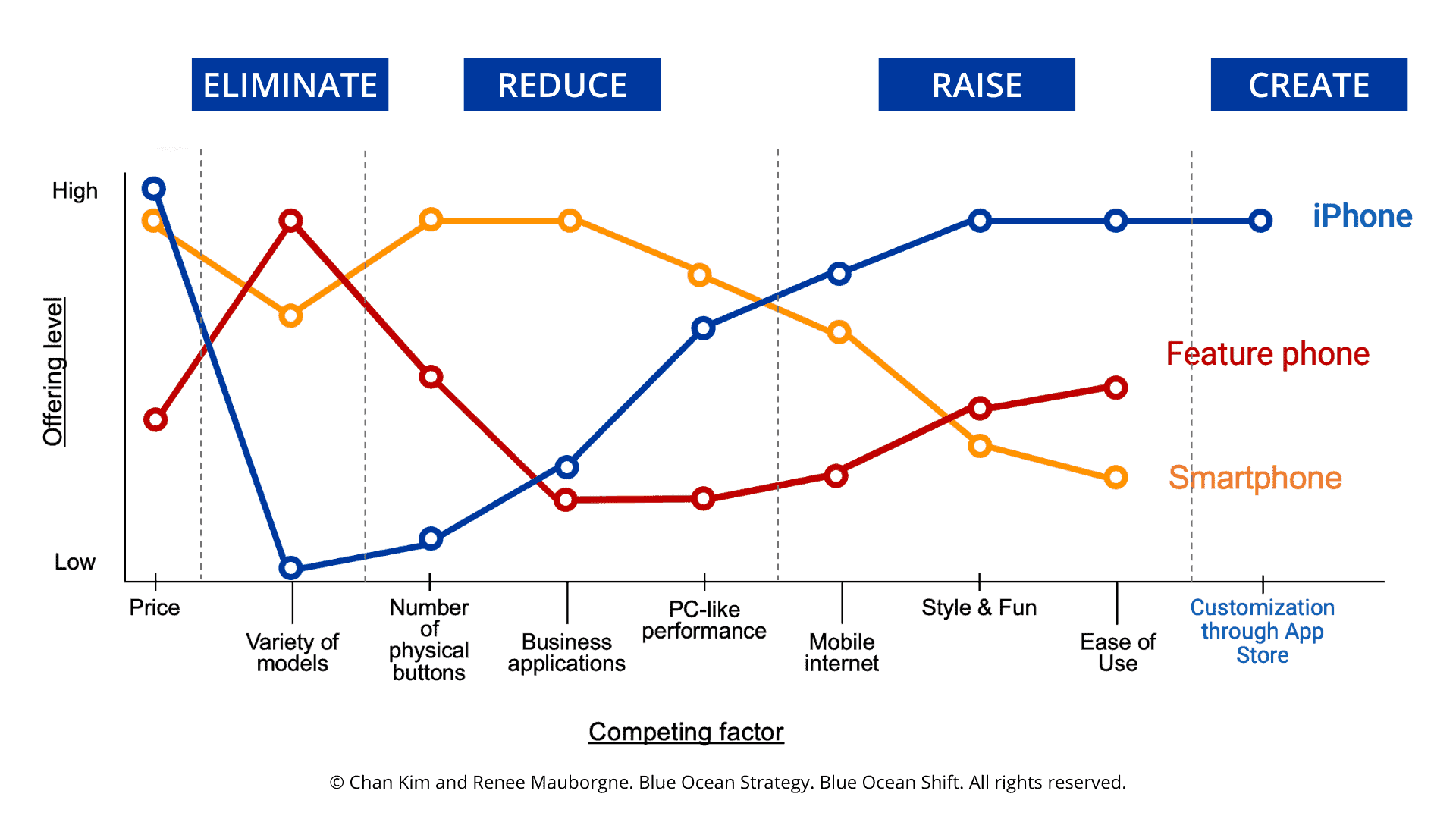

Phone manufacturers were facing a red ocean of competition by the early 2000s. Each focused on developing technology to make their phones more appealing. To create phones with more functionality, manufacturers merged MP3 players, game consoles, and digital cameras before adding email, calendar, internet browsers, and other desktop-like features.

Apple took a different approach. Rather than making the mobile phone smarter by adding more hardware features (such as a high-resolution built-in camera, email push key, and so on), Apple invested in developing a more reliable operating system and more intuitive user interface, making it easier for people to use their mobile phones effectively. By eliminating, reducing, raising, and creating factors that the industry competed on, Apple reconstructed the mobile industry to create a revolutionary new product.

Apple unveiled the iPhone to the world on January 9, 2007. The device had many of the standard smartphone add-ons, but what set it apart from the competition was its simple user interface, with only four buttons and a touchscreen instead of a physical keyboard.

Additionally, Apple hosted a marketplace for mobile ‘apps’ made by Apple or third-party programmers, allowing users to customize their phones to reflect their specific interests. Although the idea of a mobile app marketplace wasn’t new, the App Store provided the first dependable service with a diverse selection of high-quality apps.

The Strategy Canvas of the iPhone shows in one picture the current state of play in the handset industry in the early 2000. The horizontal axis shows key competitive factors the handset phone industry competed on. On the strategy canvas below, you can see how Apple’s value curve differs from its competitors.

Apple captured the three characteristics of a good strategy: it was focused, divergent, and had a clear and compelling tagline.

The Strategy Canvas of Apple iPhone

The value curve of Apple iPhone’s differs distinctively from those of its competitors in the strategy canvas.

If you’re interested to learn how Apple reconstructed industry boundaries to create new market space and unlock latent demand, check out Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne’s with Oh Young Koo case study “How Apple’s Corporate Strategy Drove High Growth“. The case examines a series of blue ocean strategic moves at Apple, including the blue ocean strategic move of iPhone, that transformed the company from a computer manufacturer into a consumer electronics powerhouse.

Medellin, Metrocable

An inspiring strategy canvas example in the public sector.

Twenty years ago, Colombia’s second-largest city, Medellin, had one of the highest murder rates in the world. Dubbed ‘Murder Capital of the World’, 16 people were murdered on average a day in 1991. The rampant violence was largely caused by drug traffickers, local gangs, and guerrilla forces.

Fast forward twenty years later. Medellin has created a blue ocean, transforming itself into a model city of innovation. So how did Medellin go from the murder capital of the world to the most innovative city of the world in under 20 years?

It all began in 2003, when mathematics professor, Sergio Fajardo, was elected mayor of Medellin, securing the biggest electoral victory in the city’s history. A new era of change was about to begin focusing on creating a leap in value at low cost, what Chan Kim & Renée Mauborgne call “value innovation“.

Among these changes, one stands out: Medellin’s pioneering ‘Metrocable’. Instead of constructing a new railway, Medellin looked across alternative industries and decided to repurpose chairlift technology, conventionally used in ski resorts. Using the existing technology, Medellin built the world’s first urban cable car system dedicated to public transport, at half the cost of a comparable railway system.

Connecting poor neighborhoods on the steep hillsides, Medellin’s transportation system transformed the city rapidly and at low cost. These days, Metrocable carries about 30,000 passengers a day traveling to and from the city center. Ultimately, the city’s innovative public transportation system became one of its most important strategies to reduce poverty and crime.

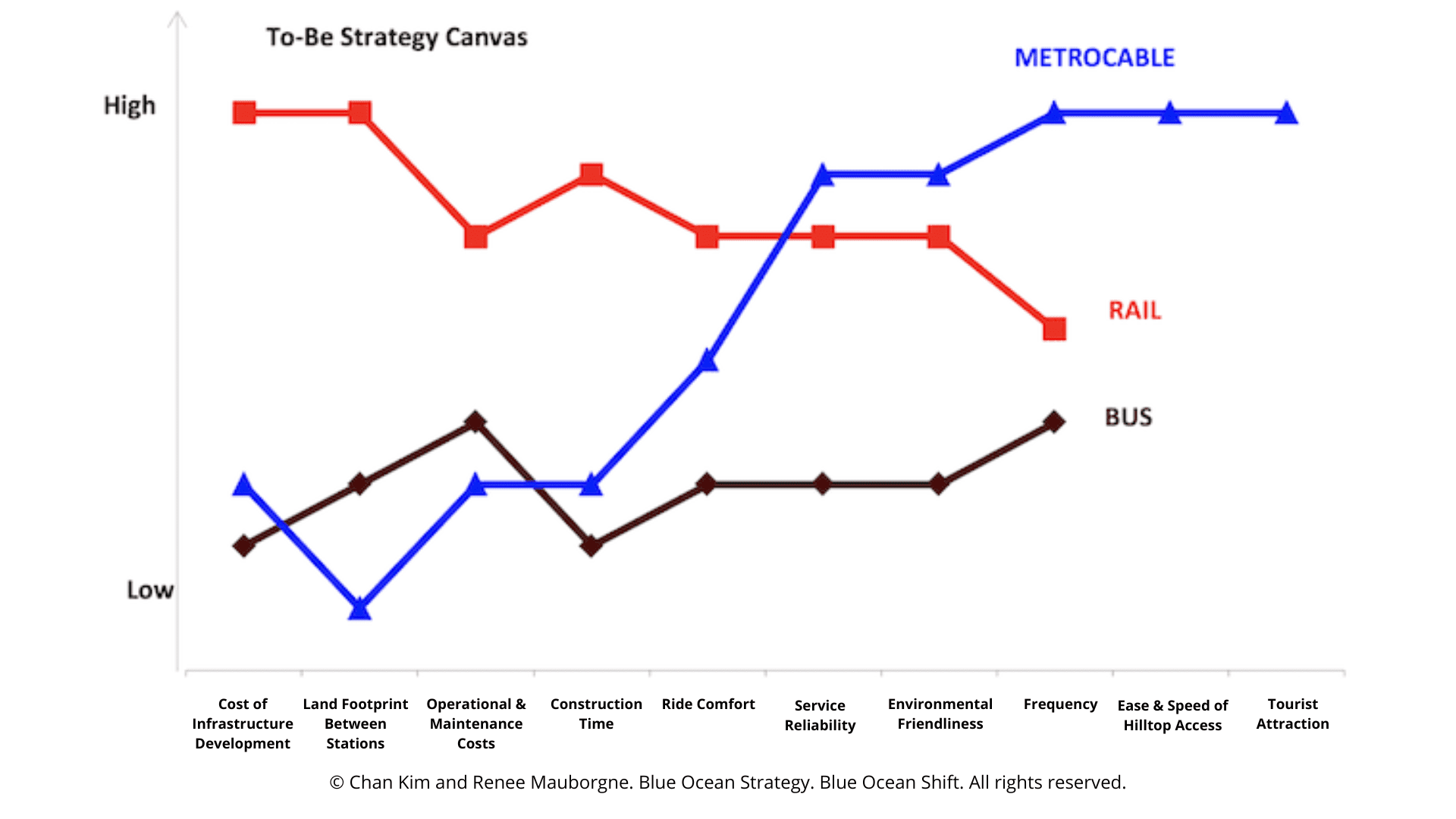

Medellin’s transit strategy showed the three qualities of a blue ocean strategy – focus, divergence and a compelling tagline.

The “To-Be” value curve shows the city focussed on providing the most frequent, reliable and environmentally friendly ride for residents to easily access the hillside barrios while creating a leap in enjoyment that made the Metrocable system an attraction for tourists in its own right. It diverges from traditional transit systems by eliminating the land footprint between stations and reducing ride comfort relative to trains.

Metrocable line K was built at a cost of $11.4 million USD per kilometre making it substantially cheaper than any form of rail transit. In addition, its operating costs are low because it requires no drivers and has just one central motor unit to maintain.

The tagline “The price of the bus, the convenience of the train, the fun of the amusement park” would succinctly communicate what Metrocable offers the citizens of Medellin. No traditional transit system can match its whimsical ride quality, rapidly delivered at a low price.

Medellin’s Metrocable To-Be Strategy Canvas

Using the existing technology, Medellin built the world’s first urban cable car system dedicated to public transport at half the cost of a comparable railway system.

By eliminating and reducing factors upon which the traditional transport industry competed but that were of little value to the citizens, Medellín was able to reduce the cost of upgrading its transit system. By raising and creating other value factors like hillside access and service frequency, the city government was able to create a leap in value for city dwellers.

To learn more how Medellin transformed itself into a model city of innovation, read our blog “Medellin: From Murder Capital of the World to the Most Innovative City in the World.”

YellowTail

Now let’s look at an exciting strategy canvas example in the wine industry.

Up until 2000, the United States had the third-largest aggregate consumption of wine worldwide with an estimated $20 billion in sales. Yet, despite its size, the industry was intensely competitive.

The US wine industry in 2000 faced intense competition, mounting price pressure, increasing bargaining power on the part of retail and distribution channels, and flat demand despite overwhelming choice.

How did [yellow tail] become the number one imported wine and the fastest-growing brand in the history of the US and Australian wine industries?

The traditional strategy of most wineries has always been to compete on the prestige and the quality of wine at a particular price point. Prestige and quality are judged by things like the personality and characteristics of a wine, reflected in the uniqueness of the soil, the winemaker’s skills, the aging process, and so on.

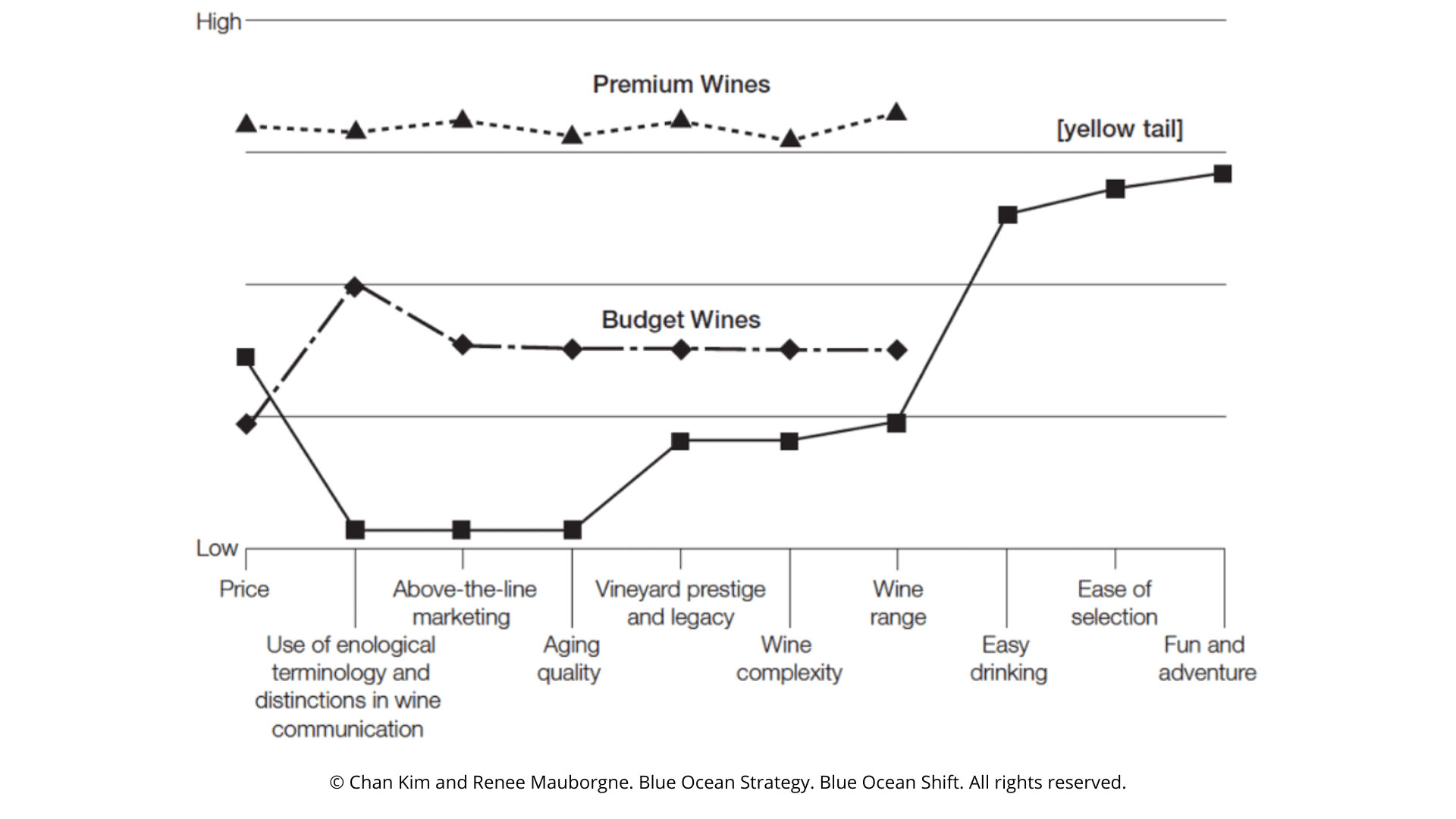

Casella Wines turned this conventional wisdom on its head. The Australian winery redefined the problem of the wine industry as how to make a fun and non-traditional wine that’s easy to drink.

The outcome of this analysis was [yellow tail], a wine whose strategic profile broke from the competition and created a blue ocean. Instead of offering wine as wine, Casella created a social drink accessible to everyone.

By looking at the alternatives of beer and ready-to-drink cocktails, Casella Wines created three new factors in the US wine industry – easy drinking, easy to select, and fun and adventure. It eliminated or reduced everything else.

The strategy canvas for [yellow tail] below quickly captures, in one simple picture, the factors an industry competes on and invests in, the offering level of each factor that buyers receive, and the strategic profile of a company and its competitors across the key competing factors.

YellowTail’s To-Be Strategy Canvas

[yellow tail] created a unique and exceptional value curve to unlock a blue ocean.

As shown in the strategy canvas, [yellow tail]’s value curve has focus: the company did not diffuse its efforts across all key factors of competition. The shape of its value curve diverged from the other players’, a result of not benchmarking competitors but instead looking across alternatives. The tagline of [yellow tail]’s strategic profile was clear: a fun and simple wine to be enjoyed every day.

To learn more about the [yellow tail]’s blue ocean strategy, check out Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne’s Blue Ocean Strategy book, where this case study is analyzed in depth.

Check out other business strategy examples to inspire you to rethink your business: “7 Powerful Blue Ocean Strategy Examples That Left the Competition Behind.”

Comic Relief

A striking strategy canvas example in the fundraising charity industry.

Let’s shift our focus from the wine industry to the charity industry.

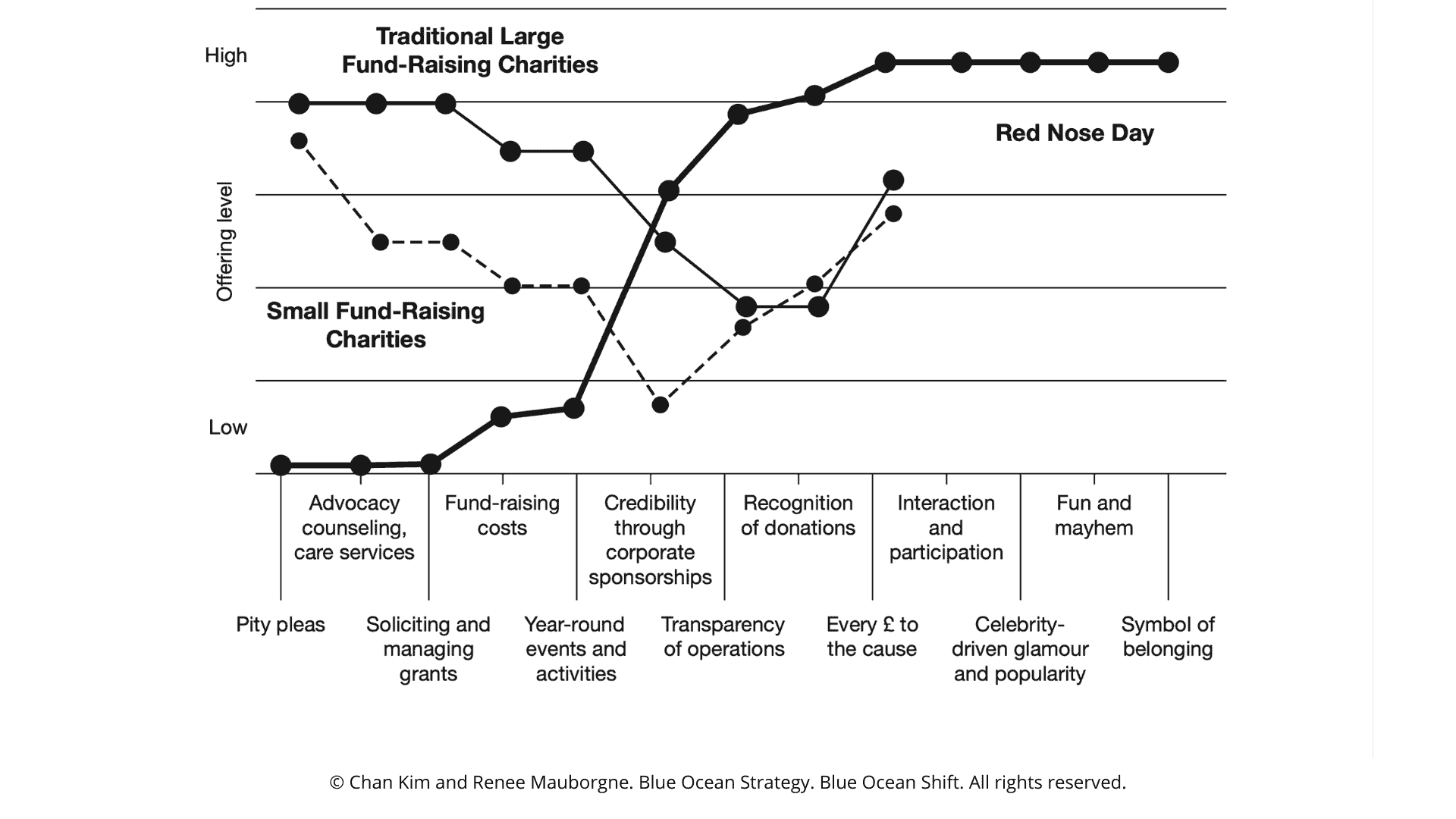

The strategy canvas of UK fundraising charity Comic Relief provides a classic example of how an organization can stand out in a red ocean of competition.

Conventional charity fundraising would provoke guilt and pity (think photographs of starving children) to raise money – mostly asking for large donations from high-income donors through year-round campaigns. Comic Relief replaced year-round fundraising with biannual events, eliminating donor fatigue.

Unlike traditional charities, Comic Relief recognized even the smallest donations, encouraging children who wanted to give their pocket money or people with modest incomes who wanted to contribute. Taking part costs as little £1 for a plastic red nose.

Comic Relief aligned its compelling value proposition with an unbeatable profit proposition. Traditional fundraising methods — hosting galas, mass-mailing, cold-calling and operating charity shops — create high overhead costs. Comic Relief eliminated 75% of costs related to traditional fundraising operations.

Let’s take a look at Comic Relief’s strategic profile and go back to the three criteria that make a strategic profile stand apart. Red Nose Day’s strategic profile meets all three criteria:

1. Its shape diverges significantly from the competition.

2. It focuses on offering buyers a leap in value (recognition no matter how small a donation, transparency, fun, sense of belonging, etc.).

3. It has a compelling tagline that speaks to buyers and honestly reflects its offering: ‘Doing something funny for money’.

Comic Relief’s To-Be Strategy Canvas

More than 30 years on, Comic Relief still has no credible imitators.

To have a better understanding on how Comic Relief made the competition irrelevant, check out our blogs:

How to Avoid Competition for Decades

Visualize Your Strategy and Stand Apart: The Case of Comic Relief.

citizenM

A divergent strategy canvas example in the redder-than-red hospitality industry.

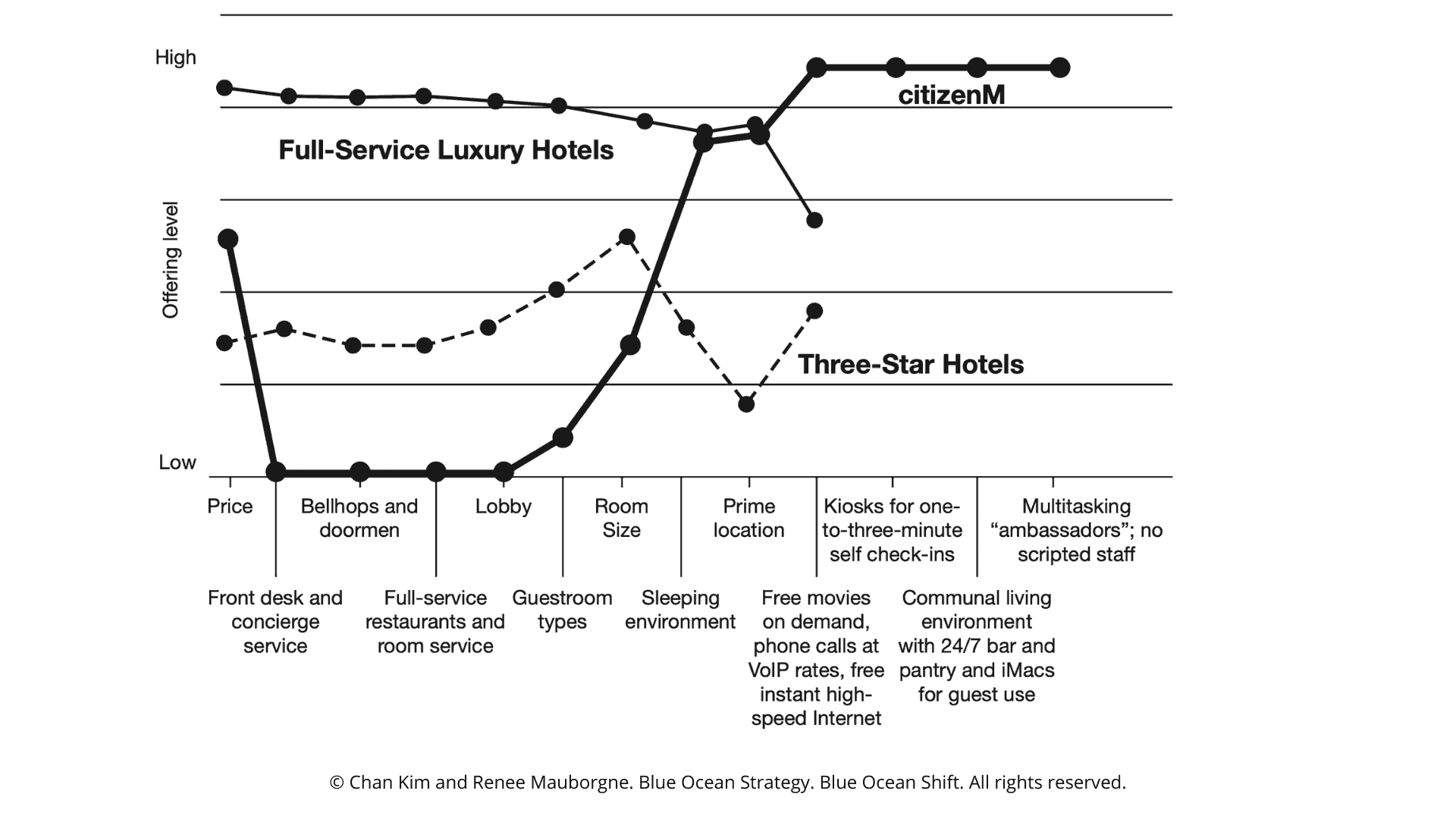

Four-star hotels offer four-fifths of what five-star hotels offer. Three-star hotels offer three-quarters of what four-star hotels provide. And so on down to one-star hotels that offer roughly half of what two-star hotels offer. In other words, they all compete on essentially the same things. “In this industry,” says Michael Levie, “people think they’ve innovated if they change the paint color on the walls or switch the type of chocolate on the pillow.”

Against this backdrop, Rattan Chadha and Michael Levie, co-founders of CitizenM wanted to create a blue ocean with a new kind of hotel chain. One that would capture the growing mass of frequent travelers – what they call “mobile citizens” – whether traveling for business or for pleasure.

The two entrepreneurs noticed that many of these “mobile citizens” were frequenting either three-star or luxury hotels. Sensing a blue ocean opportunity, they wanted to understand why frequent travelers chose luxury hotels over three-star hotels and vice versa. They identified a host of factors to eliminate, reduce, raise and create, as shown on the following strategy canvas.

citizenM’s To-Be Strategy Canvas

“Affordable luxury for the people” was the citizenM’s tagline.

CitizenM’s strategic profile meets the initial litmus test of a blue ocean offering in that it diverges from the competition; it is focused; and it has a compelling tagline that is true to the offering, namely, “affordable luxury for the people”.

CitizenM launched its first hotel in Amsterdam, opening up a new value-cost frontier of affordable luxury for frequent travelers. It has since opened hotels in prime locations of major cities like London, Paris and New York, and is continually expanding.

Blue Ocean Strategy in the Hotel Industry blog goes into more detail on how CitizenM created new market space in an overcrowded industry. And the case study is also featured in Blue Ocean Shift book, so be sure to check it out.

Learn how to draw a strategy canvas

Now it is time to learn how to draw your strategy canvas. Follow the step-by-step tutorial and download a free strategy canvas template to start.

Strategy Canvas Template

Be sure to check out Blue Ocean books for detailed guidance on how to draw the strategy canvas and use other blue ocean strategy tools and frameworks. The books will walk you through how to apply the tools to your situation, explain how to interpret the results, highlight the potential pitfalls in working with it, and discuss how to overcome those pitfalls to ensure your success.

Don’t have time to read the books? Take our flagship Blue Ocean Strategy Online Course and make your competition irrelevant.